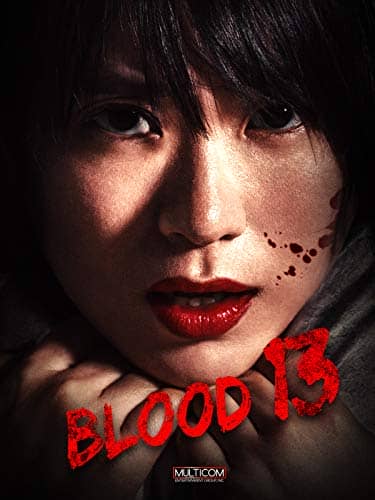

Candy Li is an up and coming director, who after getting her start in filmmaking with short films, has recently made the leap into feature film with her Chinese-language crime thriller, Blood 13. Candy Li orchestrated a female-lead action/mystery film with chilling scenes and a cast of characters that push and pull the story into thrilling and mysterious moments. Horrorbuzz discussed the inspiration for her craft and the future trajectory of this unique director.

Candy Li is an up and coming director, who after getting her start in filmmaking with short films, has recently made the leap into feature film with her Chinese-language crime thriller, Blood 13. Candy Li orchestrated a female-lead action/mystery film with chilling scenes and a cast of characters that push and pull the story into thrilling and mysterious moments. Horrorbuzz discussed the inspiration for her craft and the future trajectory of this unique director.

HorrorBuzz: What inspired you to get into filmmaking?

Candy Li: I grew up in a family of art lovers. My dad used to be a teacher and novelist. My mom loves music. Instead of talking about how the dishes were, on our dinner table my parents and I always have debates about a film we just saw. Thanks to my father’s job, he used to have a film pass to the China Film Archive, where they double featured uncensored films every Thursday night. That’s where I spent every Thursday night in high school. I still remember the great feelings when I took the night bus home after watching a good film. That’s when I decided I want to make films to make other people feel as great.

HB: How did you become involved with directing Blood 13?

CL: The screenwriter of Blood 13, Hu Tu, is a good friend of my father’s. She used to be a police officer, but she retired early in order to write what she’s seen in the police force into novels and screenplays. Hu’s daughter happened to transfer from her Beijing middle school to one in Los Angeles, and I went to help her family get situated. In the midst of buying a car and renting an apartment with them, Hu showed me the screenplay of Blood 13 and asked me if I would be interested in directing it. I was immediately hooked by the female police character, Xing Min, and many other stories Hu told me. All female police images we see in Chinese movies and televisions are all inherently brave and righteous. Xing Min happens to be a woman who’s not that perfect. She holds grudges against prostitutes due to her trauma in life, but her position requires her to represent justice. This inner conflict is very human to me, and I think it’s interesting to see if her conscientiousness prevails over her inner demons. So as Hu and I talked more deeply about the story, we pitched it to a producer I once worked with, who then helped us find the initial funding of the film.

HB: I noticed a striking use of color in some shots. How would you say color helps to tell the story of Blood 13?

CL: I wanted to portray Beijing as realistic as it can be. It’s my hometown, yet I felt I didn’t know much about how people live after midnight. The cinematography team took a few nights to wander with me in the lively bar districts of Beijing. We observed that the white fluorescent light is the most common light feature in Beijing, or maybe China in general, as I guess they are cheap and easy to replace. That kind of light always gives me a deadly feeling. And the cheapest way to make a fluorescent lightroom feel instantly cozier is to add rich, tense and bright colors. These bright but tasteless colors in the base of fluorescent lights resemble what I feel for the life of women who have to live their lives selling their bodies in the night. The world is cold, but just like everyone else, they all hope for a bright life. I wanted to use the colors close to reality as it can be to make people feel they are right there with these women.

HB: What do you wish that audiences would take away from Blood 13?

CL: Although there are many female rights movements in today’s society, some deeply rooted prejudice is still in people’s mind, even among the groups who should be representing justice. I hope this film challenges the notion that “prejudice is gone”. I wish Xing Min’s journey in Blood 13 can remind the audience that we have no excuse not to treat people equally, and to neglect is to kill.

HB: What were some tribulations or set-backs that you experienced during the filmmaking process?

CL: There were many tribulations in making this film. First of all, the discussion in the film about police being negligent on cases where victims are prostitutes was not in the censorship’s favor at all. Not only did we have to carefully word our input in the application when we turned in the script for censorship approval, we had to rewrite many scenes to be able to get the shooting permit. For example, it’s known that the police can’t let the killer escape in the end, because it shows that the police didn’t do their job right. As cautious as we were in steering the film in the direction of “admiring the police for eventually catching the murderer” rather than “their negligent in not caring about the victims”, there were still many notes given about cutting down parts that may reflect negatively on the police; so much that we had almost no way to argue but to obey in order to get the screening permit and have the film see the light of day. It was also the first time that I directed something that could be controversial, so I did not know the unspoken rules about “can’t show smoking a cigarette on screen” or “police can’t talk about the case in public spaces”, resulting eliminations of many scenes that I think would make much more sense if they were still in the film. And that’s just the easiest thing to do – to change some scenes. I knew if I had neglected the comments and continued distributing the films without the license, I could be banned from making films. In the end, we have to balance between compromises on these scenes or details, or having this film or myself banned completely. Although it’s a shame that some scenes are cut or some lines are not read, I was glad that we pushed the envelope and our film had made it this far.

HB: What were some highlights that you experienced during the filmmaking process?

CL: I had a great team. The script knocked open many doors, including my lead actress, Huang Lu, who has appeared in my great films internationally. It was the most fun working with her as she always gave me great suggestions on how to enrich the characters by small details. My producer was also supportive in my creative decisions. I was also able to bring half of the crew that I’ve worked with while studying in the US to China, and all of them worked very hard with very limited budget and long hours. All my local Chinese crew was hardworking as well. Both the US and Chinese crew worked very well together despite the language barrier. It was a very unique collective process. And I was very touched by everyone in the team who cared so much about the quality of the film and they had the passion to help me make the best of it.

HB: What are the most notable acknowledgment and awards that you have received for this film?

CL: We were happy to participate in the 8th Beijing International Film Festival, and were featured in the “Female Power” section screenings along a few great films in the history with female protagonists. The judge of the film festival that year was Wong Kar Wai, who gave a shout out to our film at the premiere, as I was one of the two female directors to bring our debut feature films to the film festival.

HB: Do you have plans for any next projects, and if so, how will your experience making Blood 13 inform those following projects?

CL: While talking with production companies about potential work-for-hire projects, I am also writing the screenplay of my next film. I love being inspired by the text of the screenplays, but I also hope to learn to tell my own stories, and find my own voice that’s unique in the world.

Candy Li, who credits her personal favorite film to Lou Ye’s 2006 romantic-drama Summer Palace, seems to be a director to watch for dramatic, epic, passionate film projects. To follow Blood 13 and its director, Candy Li can be found on Instagram @powerpuffgirlcandy