The clanging of metal begins to fill my ears as soon as I walk into town. The blacksmith seems to be starting early today, busy making nails for the nearby carpenter. After walking a few more feet, the aroma of freshly baked bread fills my nose. It looks like the bakery is at it, too. A few of the women from the village wave to me as I walk by, dressed appropriately for the 1850s; their hoop skirts go down to their ankles, and white bonnets keep their hair out of their eyes while they work. Nearby, the church bell tolls to let us know it is 9 AM.

And so begins another day in Allaire Village.

No, I didn’t hop into my DeLorean, and travel back in time to see these sights. I merely got into my 2001 Alero, and traveled down CR-524 to Historic Allaire State Park, located in Howell, NJ.

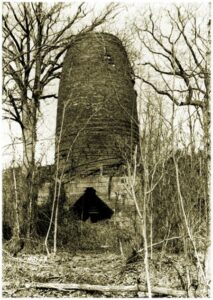

Allaire is one the nation’s ‘living history’ parks. Run by the nonprofit organization Allaire Village Inc., the park sponsors more than 40 programs and events annually, including living history events, antique shows, arts and craft shows, and flea markets. You can experience how life was lived back in the early 19th Century almost every day of the year, when volunteers assume their roles of townspeople and take you on a tour of the Howell Works, New Jersey’s finest example of the bog iron industry.

And, if some of the stories are believed to be true, you may experience some of the Village’s ghostly inhabitants as well.

But before you can understand the village’s other populace, you need to know a little bit about where they came from.

James Peter Allaire was a jack-of-all-trades. Known as a philanthropist, engineer, steam engine and boiler manufacturer, he was an all-around businessman. He purchased the land that would become the Howell Works in 1822. He let a Company Manager run the day-to-day operations for him while he only visited the site every few months. The Howell Works was located in Pine Barrens, a remote bit of land in the heart of New Jersey. Because of this isolation, Allaire had to consider developing a self-sufficient community at the site. This community would eventually come to include a carpenter shop, bakery, blacksmith, various mills, a general store, a school, a church, and row houses for the workers and their families. Amazingly, most of these buildings still stand today.

At the time of the purchase, Allaire and his family lived in New York City for many years. That is, until, unforeseen events forced them to move. In 1832, a severe cholera outbreak was set loose in New York. His wife, Frances Duncan, was already an ill woman. It is thought now that she may have had tuberculosis. Allaire feared for the safety of his family, and the health of his wife, and decided to move them all to the Howell Works.

There was a farmhouse on the property, the largest residence on the land, which Allaire choose for his family’s new home. Before they moved in, Allaire had some renovations completed, to make it more accessible to his family. The home would eventually come to be called ‘The Big House,’ as people affectionately call it today. The Allaire’s lived there with their two daughters, Maria Haggerty & Frances Allaire Roe, their granddaughter Fanny Roe, and two distant cousins. To help to aid with the care of his wife, Allaire had his first cousin once removed, Calicia Allaire Tompkins, come to stay with the family.

Although Allaire thought the fresh air would help his wife get better, it, unfortunately, did not last long. Frances Duncan died in the Big House on March 23rd, 1836. The death of his wife of 32 years hit Allaire quite hard. It is said that he stayed by her empty bedside for two months after she had passed, grieving at her loss. When business eventually forced him out of mourning, he realized that, despite his tragic loss, a ray of light did shine in his life. His daughter, Maria Haggerty, wed the manager of Allaire Works in New York City, Thomas Andrews, in June of that same year. After the wedding, Allaire returned to New York City, not wanting to continue living at a place that would constantly remind him of his deceased wife.

Unfortunately, the good news did not last for him. Allaire suffered from severe financial loss when several of his steamboats ran aground. The cost of repair was enormous, and Allaire had little insurance on his boats. On top of that, about 90 lives were lost in the accidents. When this country’s first great depression began in the late 1830s, the need for the products Allaire produced evaporated. Also, iron and coal deposits found in Pennsylvania helped usher in the end of the bog iron industry in New Jersey. Shortly after 1849, the Howell Works Company was officially declared bankrupt.

Having lost his business, and his New York home in the process, Allaire permanently retired to the Big House around 1851. His cousin and new wife Calicia, whom he married in 1847, joined him, along with their son Hal. It was there that they lived out the rest of their lives. James Peter Allaire passed away quietly at the age of 73 on May 20th, 1858, on the Howell Works property.

In 1941, the property was deeded to the state of New Jersey, with the goal of turning it into a living history museum. It was renamed Allaire Village, and is there today to help educate visitors of the life and times of James P. Allaire. Visitors today can experience the way life was once lived in the bog iron community.

Of course, what would any historical village be without a few of its former residents still lingering around? Many visitors (and volunteers) report strange experiences while visiting this once thriving community.

One of the most prominent ghosts is that of Hal Allaire, the last son of James Peter Allaire. He is rumored to haunt the Big House, and has a habit of playing tricks on the costumed interpreters that work in that house. Hal has been known to move books and other household objects around. He apparently also has a love for playing with candles. I spoke to a few of the volunteers at Allaire, and many of them had very interesting stories to tell.

One volunteer told me that one night, while she was giving a tour of the Big House, some visitors reported that a locked bookcase that they had passed when the tour began was now wide open. The tour guide quickly closed the case again, and resumed her stories about the house.

“After I regained everyone’s attention, we began to notice the candles were flickering, but not like normal flickering. The flame would almost go out and then go bright again, repeatedly, like someone was taking all the oxygen away from it,” she said. “Incidents like this aren’t alone. Many other instances like these happened often at the mansion. Other times, people would report seeing candlelight and faces looking back at them in some of the windows of the Big House, long after we had closed down for the night. We would also notice things going missing, chairs moved around, strange voices, and images in the mirror that weren’t actually there. None of it was ever threatening, though.”

In fact, many of the surviving buildings are said to be home to some happy haunts. The Visitor’s Center, for example, used to be the former residences for the ironworkers and their families. Many visitors to the park complain of cold spots while being in there. Some park volunteers refuse to go into center’s basement at night, because they get the feeling that someone is watching them.

Another ghost said to haunt the grounds is Oscar Smith. Oscar supposedly likes to play tricks around the Manager’s house by using the children’s blocks on the second floor to spell out his finance’s name. One worker even reported seeing him while she was waiting for her friend to come pick her up. Thinking it was her friend, she followed after him, only to see him disappear in thin air! The park system itself doesn’t ‘officially’ recognize the existence of these otherworldly occupants, but most of the workers have their own unique stories to tell.

So, if you have a day to spare this week, take the drive out to Allaire State Park. The history of the place alone should be enough to entice you to visit. If that’s not enough, the park also boasts a small steam powered train ride, and plenty of nature trails to occupy your time. Though Allaire Village is a state park, many of its areas are off limits to guests. If you decide to visit, please do not trespass into areas that are off limits. Many areas of the park are in various stages of renovation, and some are quite dangerous if you take a step in the wrong direction.

And on your way out, be sure to say goodbye to the residents of the town: both the living…and those who decided to stay around.

![THE FIELD Delivers an Atmospheric Haunting [REVIEW]](https://horrorbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Field-500x383.jpg)