Dario Argento’s name has become synonymous with Italian Horror. The writer-director’s body of work—ranging from classics like Suspiria and Deep Red (Profondo Rosso) to critical and commercial flops like Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D—retains a fervent fanbase and continues to inspire filmmakers around the world.

name has become synonymous with Italian Horror. The writer-director’s body of work—ranging from classics like Suspiria and Deep Red (Profondo Rosso) to critical and commercial flops like Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D—retains a fervent fanbase and continues to inspire filmmakers around the world.

Scholarship within the past 30 years by Maitland McDonagh (Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento), Mikel J. Koven (La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film), Ian Olney (Euro Horror: Classic European Horror Cinema in Contemporary American Culture) and others have argued for the importance of these Italian horror cinemas in academia. When news initially broke that Argento was writing his memoirs, there was much anticipation. Fast forward to last August when readers got a chance to purchase a copy and read the words of the dubbed “Italian Hitchcock.”

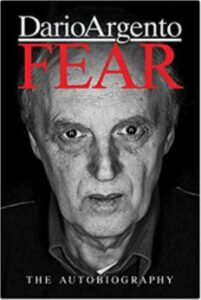

Overall, Fear: The Autobiography of Dario Argento is a satisfying read. Structured chronologically, the book is full of anecdotes, personal reflections, and candid observations on cinema. Although some memories or particulars of film productions may be familiar to people who have listened to some of his interviews or viewed documentaries about the production of certain films, the amount of detail Argento incorporates in the book help flesh these areas out.

Most welcome are passages about Argento’s childhood and early career as a film journalist and screenwriter. Who knew that he was a Boy Scout? Others may appreciate his recounting of developing the story for Once Upon a Time in the West with Sergio Leone and Bernardo Bertolucci.

For all the wealth of information present within a slim 288 pages, there is a chance some readers may be disappointed. Those expecting an uncensored account of salacious details about Argento’s social life should look elsewhere. Fear is not your typical memoir about sexual affairs, drug use, or tabloid scandals. When he does frankly address past personal or professional relationships, he still approaches them with a certain amount of respect. Instead, Argento mostly focuses on his creative process and his personal outlook on life.

That being said, in the book Argento does engage with the criticism directed toward his work. This includes claims of misogyny and the questionable casting of his daughter in various violent or sexually charged films. Indeed, Argento has directly addressed criticism in his films—see the scene in Tenebrae where a critic lashes out at horror-mystery writer Peter Neal about the misogynistic tone of his latest novel, or the needles taped under Betty’s eyes in Opera referencing the fact that audience members tend to look away from his use of graphic violence. However, his responses here either are dismissive or tend to reiterate lofty counterarguments from the past. This approach may leave a sour taste in the mouths of some readers who may have been hoping that, with time, Argento would be more receptive toward these perceptions.

Overall, Argento’s autobiography is a simultaneously fascinating and frustrating read. Fear may appeal most to fans and scholars of his work, as long as certain expectations are kept in check.

Rating 7 out of 10 stars