Almost four years ago I clicked “purchase” on the computer screen, not knowing what was in store for me.

I rolled this decision around in my head for a few days afterwards, watching the time disappear, mapping out my route to the location, making sure to tell a friend where I’d be.

Finally it was time. “Blackout” awaited.

I walked to the Red Line from my Hollywood apartment to go downtown. Everything was heightened. Everyone who crossed my path could be in on it. The quick glance from the man on the subway. The teenagers chatting as I walked past them. My senses were screaming. My hair stood on edge.

When my turn came I was pulled into “Blackout” and my world changed.

The violence, the assault, the horror of it all.

At one point I had to put my hand into a toilet filled with vomit to dig around for a pair of keys. It was revolting and awful. “How did it come to this?” I wondered. “What have I done?”

When I emerged at the end of the experience I willed myself to smell my hand — I had to know if it was true — only to realize what covered my hand wasn’t vomit: it was oatmeal.

Oh.

It was all a trick. It was smoke and mirrors. Theater at an intimate and terrifying level, heightened to the edge of abuse.

I left in a daze, calling my best friend Mike, who had asked for an immediate reaction to what I’d just been through when (and if) I survived.

I don’t remember that conversation, but I do know what came next.

“Blackout” changed me. The direction of my life was profoundly shaken by that night. “Blackout” spoke to me the way that, I suspect, it speaks to most of the people who will be reading this.

“Blackout” is The Thing that decidedly isn’t for everybody, but for some of us it just makes sense.

A tweet came out not too long after my first “Blackout” that a documentary crew looking for people to interview who had gone through the experience. I responded, and soon found myself in a garage in Pasadena telling the filmmakers what had brought me into “Blackout” and what continued to draw me to it.

(L-R) Allison Fogarty, Bob Glouberman, Rich Fox, Kris Curry, Russell Eaton, and Abel Horwitz attend the “The Blackout Experiments” Premiere during the 2016 Sundance Film Festival at Egyptian Theatre on January 24, 2016 in Park City, Utah.

(Jan. 23, 2016 – Source: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images North America)

The documentary was spearheaded by a husband and wife team: Rich Fox was the director and Kris Curry was the producer. Nice people, if not a bit suspect. Who were they, really? What was their connection to “Blackout”?

They’d laugh when I expressed concern over their motivation and they’d ask me to say it again, this time on camera. In fact, any time these thoughts popped into my head they requested me to take out my phone and record myself asking these questions.

Who were they? What was “Blackout”?

This went on for a few years.

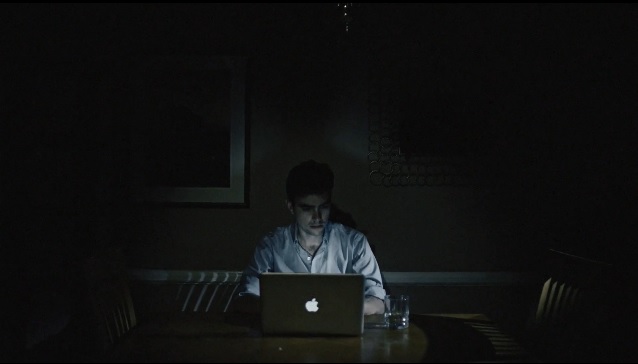

Sometimes it would be months without hearing from them. Sometime they’d ask me to record voice memos to them, or ask if they could come into my apartment and film me looking at my computer to recreate the moment when I first purchased tickets for “Blackout”.

And then one day last December, Rich wrote me e-mail: “Something big might happen tomorrow.”

That “big” was Sundance. The film was ready and would premiere at Sundance, during the Midnight Selection.

Woah.

I knew I had to be there. Mike said he’d come, too. After all, he’d been there since the beginning. We roped in our girlfriends and took a day off of work to drive to Park City.

On Friday night we left Los Angeles. We drove four hours to Las Vegas and slept at a friend’s house. The next day we drove another six hours to make it to the festival. Our girlfriends — both Southern California born and raised — were wary about the snow, which I found kind of funny.

Sundance was surreal. That place where I’d always wanted to be, but now that I was here it was a bit overwhelming. I tried to leverage my inclusion in a film into party invitations, but being the fourth lead of a documentary doesn’t mean much when Daniel Radcliffe and Nick Jonas have films premiering there, too.

Rather, we spent most of our time there walking up and down main street. Popping into branded storefronts hoping to score free coffee, water bottles, beer. Anything, really.

I was recognized once, based off of the clip of me staring at my computer. That was surreal. I guess people were genuinely curious about the film.

Finally the time came.

I had to remind myself to stay present. To not worry about the parties we didn’t get into or the snowy roads we’d have to drive to get out of Park City. That ultimately we had come to enjoy the film. To celebrate the hard work of the production team and the subjects in front of the camera. To celebrate “Blackout” for all of its violence and catharsis.

When the lights went down and the film began I suddenly felt exposed. Far more than I had thought I would.

Going through “Blackout” is a personal experience. It is an individual walk through something intense. To see myself (and my fellow “survivors”) on screen was scary.

Afterwards we stood onstage for a Q+A. The “Blackout” creators, Josh Randall and Kris Thor, were onstage with us as well. For me it was a bit tense to be that close to them.

Reviews have started to come out about the film, calling it “faux” or a “mockumentary”. It’s odd to read that critique because I know that the film is real. I was there. That’s my face in front of the camera and that’s my name in the credits.

Yet at the same time I understand where these reviewers are coming from…”Blackout” can’t be real. It’s too intense. Too strange. If you don’t “get” the appeal of “Blackout” then why would you think anyone would be so willing to subject themselves to its violence?

On Monday we drove home. On Tuesday I was back in the office. Back to my day job.

“How was it?” coworkers would ask. “Did you have fun at Sundance?”

I don’t know, honestly. I’m thrilled to have gone, thrilled to have participated. But also nervous. What comes next?

I remind myself that almost four years ago I bought a ticket not knowing what would come next.